Daniel Mosher served as a sailor during the Revolutionary War. He was taken prisoner by the British and was held on board the infamous Old Jersey prison ship for 18 months. He survived.

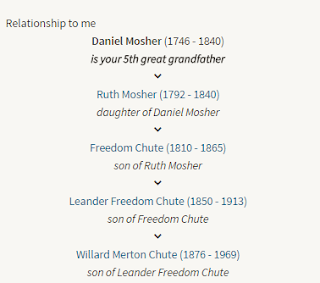

Daniel

Mosher (father of Ruth Mosher, wife of Moses Chute) was

born on December 30, 1746, in Dartmouth, Massachusetts to Ephraim and Eunice. He

married Elizabeth

Macomber on December 30, 1764, in his hometown. He initially moved to Rome, Maine with several of his sons, purchasing land from the proprietors. He moved to Ohio in 1816. They had 10 children in 26 years. He died on

February 7, 1840, in Athens, Ohio, at the impressive

age of 93, and was buried in Morgan, Ohio.

When the

American Revolution began, the British used Old Jersey as a prison ship for

captured Continental Army soldiers, making her infamous due to the harsh

conditions in which the prisoners were kept. Thousands of men were crammed

below decks where there was no natural light or fresh air and few provisions

for the sick and hungry. James Forten was one of those imprisoned aboard her

during this period. Political tensions only made the prisoners' days worse,

with brutal mistreatment by the British guards becoming fairly common. As many

as eight corpses a day were buried from the Jersey alone before the British

surrendered at Yorktown on 19 October 1781. When the British evacuated New York

at the end of 1783, Jersey was abandoned in the harbor, having had

approximately 8,000 prisoners on board.

When the

American Revolution began, the British used Old Jersey as a prison ship for

captured Continental Army soldiers, making her infamous due to the harsh

conditions in which the prisoners were kept. Thousands of men were crammed

below decks where there was no natural light or fresh air and few provisions

for the sick and hungry. James Forten was one of those imprisoned aboard her

during this period. Political tensions only made the prisoners' days worse,

with brutal mistreatment by the British guards becoming fairly common. As many

as eight corpses a day were buried from the Jersey alone before the British

surrendered at Yorktown on 19 October 1781. When the British evacuated New York

at the end of 1783, Jersey was abandoned in the harbor, having had

approximately 8,000 prisoners on board.

One of the most

gruesome chapters in the story of America's struggle for independence from

Britain occurred in the waters near New York Harbor, near the current location

of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. From 1776 to 1783, the British forces occupying New

York City used abandoned or decommissioned warships anchored just offshore to

hold those soldiers, sailors and private citizens they had captured in battle

or arrested on land or at sea (many for refusing to swear an oath of allegiance

to the British Crown). Some 11,000 prisoners died aboard the prison ships over

the course of the war, many from disease or malnutrition. Many of these were

inmates of the notorious HMS Jersey, which earned the nickname "Hell"

for its inhumane conditions and the obscenely high death rate of its prisoners.

'When

a man died he was carried up on the forecastle and laid there until the next

morning at 8 o'clock when they were all lowered down the ship sides by a rope

round them in the same manner as tho' they were beasts. There was 8 died of a

day while I was there. They were carried on shore in heaps and hove out the

boat on the wharf, then taken across a hand barrow, carried to the edge of the

bank, where a hole was dug 1 or 2 feet deep and all hove in together.'

In 1778, Robert

Sheffield of Stonington, Connecticut, escaped from one of the prison ships, and

told his story in the Connecticut Gazette, printed July 10, 1778. He was one of

350 prisoners held in a compartment below the decks.

"The

heat was so intense that (the hot sun shining all day on deck) they were all

naked, which also served them well to get rid of vermin, but the sick were eaten

up alive. Their sickly countenances, and ghastly looks were truly horrible;

some swearing and blaspheming; others crying, praying, and wringing their

hands; and stalking about like ghosts; others delirious, raving and

storming,--all panting for breath; some dead, and corrupting. The air was so

foul that at times a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which the

bodies were not missed until they had been dead ten days."[13]

By the end of the

war in 1783, it was estimated that roughly 8,000 men and boys had died of

disease, starvation, and maltreatment aboard New York’s prison ships: that’s

8,000 out of the estimated 25,000 Americans who died in the entire war.

From

<http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/59062175/person/40057691268/mediax/3?pgnum=1&pg=0&pgpl=pid%7CpgNum>

Captain T. Dring, who survived imprisonment on the Jersey,

discussed the prisoners’ celebration of July 4th on the ship. They stored

rations for the celebratory occasion, and during their daily furlough on the

top deck, they ate, drank, and made merry, much to the chagrin of their British

captors. Before long, tempers flared, and the Americans were forced back below

deck by the Redcoats, who slashed haphazardly with their bayonets in their

frustration at the prisoners’ refusal to stop singing patriotic songs. Captain

Dring recounts:

“It had been the usual custom for each person to carry below,

when he descended at sunset, a pint of water, to quench his thirst during the

night. But, on this occasion, we had thus been driven to our dungeon three

hours before the setting of the sun, and without our usual supply of

water. Of this night I cannot describe the horror. The day had been

sultry, and the heat was extreme throughout the ship. The unusual number of

hours during which we had been crowded together between decks; the foul atmosphere

and sickening heat; the additional excitement and restlessness caused by the

unwonted wanton attack which had been made; above all, the want of water, not a

drop of which could be obtained during the whole night, to cool our parched

lips; the imprecations of those who were half distracted with their burning

thirst; the shrieks and wails of the wounded; the struggles and groans of the

dying; together formed a combination of horrors which no pen can describe”

The Prison

Ship Martyrs' Monument in Fort Greene Park, in the New York City borough of

Brooklyn, is a memorial to the more than 11,500 American prisoners of war who

died in captivity aboard sixteen British prison ships during the American

Revolutionary War.[1] The remains of a small fraction of those who died on the

ships are interred in a crypt beneath its base. The ships included the HMS

Jersey, the Scorpion, the Hope, the Falmouth, the Stromboli, Hunter, and

others.[2][3] Their

remains were first gathered and interred in 1808.